For about as long as there have been planes there have been entrepreneurs and engineers trying to make aviation more accessible to the masses. Today, there are companies promising to make the sky for everyone with electric VTOLs that are too expensive with far too many limitations to achieve that promise. Back in the 1960s and 1970s, there was another engineer promising to make aviation more accessible. As homebuilt plane publication Kitplanes wrote, Jim Bede was an aviation engineer with big dreams. He got his engineering degree in 1957 and went off to work for North American Aviation. There, he used his talents on the A-3 Vigilante, F-4, and F-100. His stint at North American Aviation didn’t last long, and Bede eventually set his sights on making general aviation cheaper and easier. Bede’s approach was different. Aircraft manufacturers normally sold factory-built planes. Bede? He’d have pilots save money by building their planes themselves from kits. Homebuilt planes weren’t new–they date back to the birth of aviation–but offering a homebuilt plane as a kit with instructions was a novel idea. Bede Aircraft Corporation was founded in 1961 and its founder got right to work. First came the BD-1. As noted by Kitplanes, this homebuilt consisted of 385 distinct parts, 175 of which were interchangeable. This made the BD-1 simple and cheaper to manufacture, perfect for the home builder. Bede designed the BD-1’s large parts to be bonded together, something that was pretty far out in general aviation at the time. The standard at the time was to rivet parts together. Bede touted the BD-1 as the everyman’s airplane that anyone can build it and fly. Thinking about this kind of buyer, he designed the wings to be easily detached so the plane could be stored somewhere cheaper than a hangar. Bede was even going to open a flight school to teach pilots how to fly their finished planes. Unfortunately, the BD-1 required more capital and time than promised. According to a 1989 edition of pilot publication Aviation Consumer, a journalist took over the BD-1 project, kicking Bede out and renaming the company to American Aviation. The design was modified without Bede’s input and designated the AA-1. The plane would later be picked up by Grumman and go on to be a success. Bede didn’t let that stop him and he continued to create wild aircraft. Next came the BD-2, a powered aircraft that looked like a glider, had an incredible 565-gallon fuel capacity, and set a distance record, traveling 8,973 miles without refueling. Then came the BD-3, a concept for a six-place pusher (propeller placed in the rear) aircraft. Then there was the BD-4, which became the first of Bede’s kit designs to reach the market under his name. Bede touted the aircraft’s ease of construction; builders would only need to slide plastic panels over the wings rather than fuss around with rivets or stitching. And the build was spaced out through seven separate kits that were shipped to pilots’ doors. When they finished one kit, they’d work on the next. The BD-4 provided Bede with the funds for what came next. And this one wasn’t going to look like a boxy Cessna 172.

The BD-5 Promise

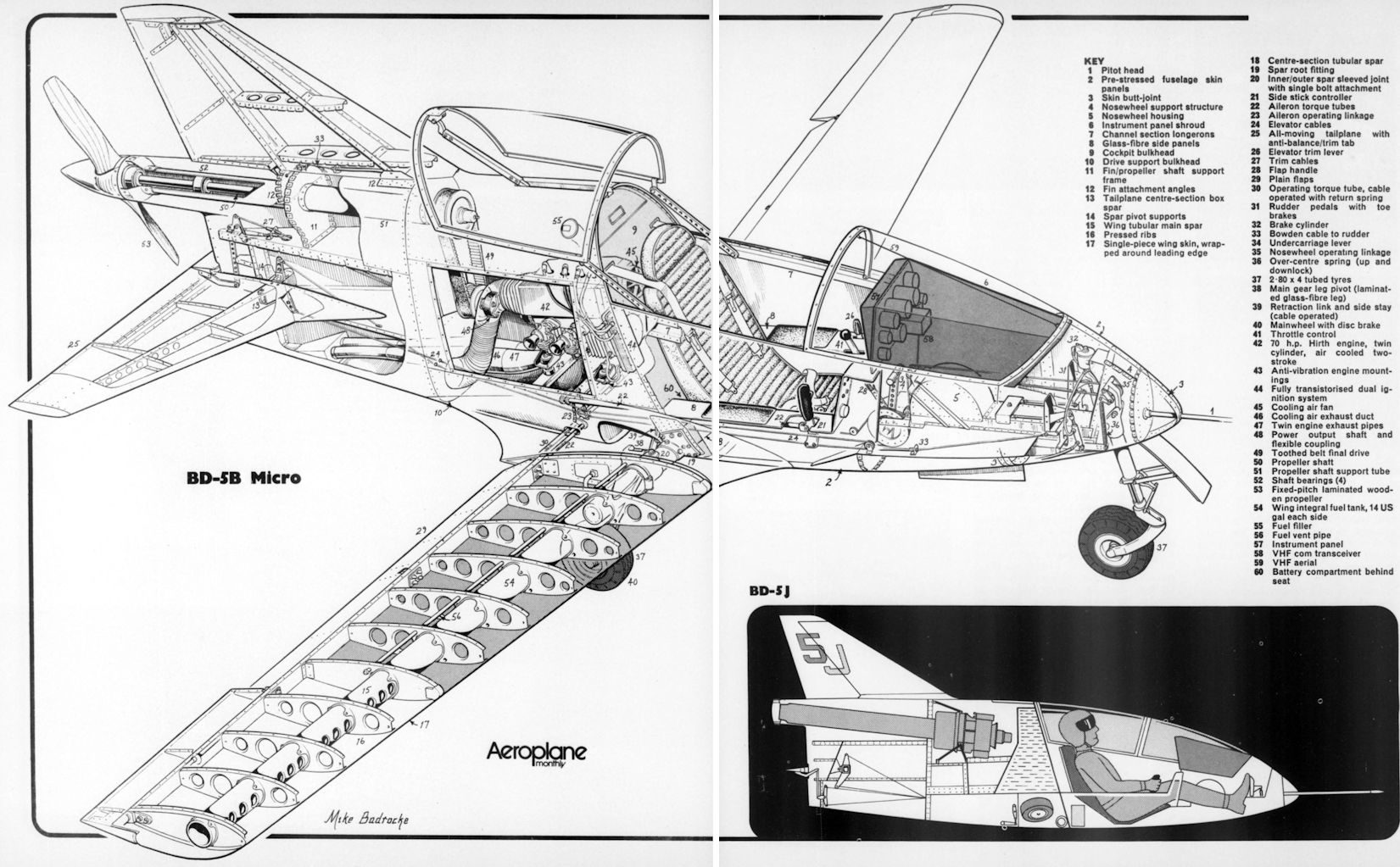

In summer 1971, Jim Bede arrived at an Experimental Aircraft Association Oshkosh fly-in hauling in an aircraft design prototype that shocked the crowd. His plane looked like a rocket, a tiny rocket that you put together at a massive discount over buying something that looked far more boring and built in a factory. Pilots had already placed orders as far back as February of the same year, and by the end of the summer 1971 Bede had 800 orders for a plane that didn’t yet exist. A September 1973 issue of Flying Magazine allured readers with something that sounded almost too good to be true. They could buy a plane that could fly nearly 200 mph with an engine that made just 40 horsepower. And the plane could go over 200 mph with a 55 hp or 70 hp engine. Oh, and it came in at just 460 pounds. This plane would cost less than $6 an hour to run, get 38 mpg, and cost $2,965. Or at least, that’s what Jim Bede said. Earlier ads had an even lower price. Bede started work on this revolutionary sport plane concept in 1967. Flying Magazine noted in its piece that the BD-5 Micro’s cockpit design takes inspiration from the Schleicher AS-W15 glider. The pilot–the sole occupant–would sit slightly reclined, commanding their aircraft using a novel side stick to their right. And that pilot wasn’t supposed to work too hard to build it, either. Bede originally saw pilots putting it together in as little as 600 to 800 hours thanks to a fiberglass fuselage attaching to an aluminum frame. The aircraft’s test pilot, Les Berven, gave glowing praise to the BD-5, calling it the closest thing to perfection that a pilot could experience.

Production Headaches

On September 12, 1971, The first prototype, N500BD, lifted just a few feet off of the ground. It was powered by a 36 hp Polaris snowmobile engine and the small hop revealed that the plane was nowhere near production-ready. At the time, it was determined that the carburetor and nose gear needed changes. Then, during a high-speed taxi, the plane nosed up and lifted off of the tarmac all on its own, surprising its test pilot. As Flying Magazine reported, it was determined that the plane’s original design–which involved a V-tail for less drag–was unstable. And that sleek glider-inspired cockpit was way too small. Bede and his team also that the original prototype’s fiberglass fuselage made changes difficult, so the design was changed to metal. He also ditched the V-tail for a more conventional horizontal and vertical stabilizer, albeit with the horizontal stabilizer at a high sweep. But even that brought its own problems, as testing showed that the propeller caused interference with the redesigned horizontal stabilizer. Moving the stabilizer up six inches was the cure. Next came the second prototype, N501BD. Bede would realize that this project had become far bigger than he could handle and in 1972, Burt Rutan became Director of Development. Rutan–nowadays a famed aerospace engineer with a portfolio full of innovative designs–left his position as a civilian flight test project engineer for the U.S. Air Force to lead the department. N501BD featured the new metal design and a 40 hp Kiekhaefer snowmobile engine, but still had stability problems. The development team was eventually forced to ditch the high-sweep of the horizontal stabilizer for a flatter design. Kiekhaefer was supposed to supply the plane’s engines, but Bede failed to secure the deal. The engines were swapped out for 40 hp Hirth Motoren two-strokes, also meant for snowmobiles. Finally, in May 1972, 15 months after the first deposit was placed, the BD-5 Micro made its first real flight, climbing higher than just a few feet. And even then, as a BD-5 buyer in Aviation History Magazine notes, the prototype’s engine overheated and filled the cockpit with smoke. Rutan reportedly said that the program involved many engine failures. Development would see other problems, too, such as a flight stick that was too light an engine that ran too rich. The second prototype had two forced landings. One happened after its engine seized, and on the other, the engine quit after it received too much fuel and too little air. Both landings were rough on the little prototype. In the first, the aircraft overran the runway, causing the nose gear to buckle. In the second, the test pilot landed on a road, buckling the undercarriage and damaging the fuselage. Bede decided to move on to a third prototype instead of repairing the second again.

Kits Begin Reaching Customers

In early 1973, and before the third prototype was finished, Bede began shipping out the first kits to BD-5 Micro buyers. The idea was that builders could work on their BD-5 Micros right away and perhaps even have their plane ready before the engine showed up. Some of these kits had completely random parts without instructions for how to put them together. Owners complained about the confusing parts that they received. Around this time, Burt Rutan was reportedly concerned with Bedes’ operation. He pointed out that the BD-5 Micro had barely flown for two minutes, yet they were already shipping kits to customers. The third prototype, N502BD, first flew in 1973 and introduced the team to new problems. A change from a variable belt drive to a direct belt drive led to severe vibrations and the Hirth engines continued to fail, forcing the prototype into more emergency landings. And those Hirth engines were too weak to provide the promised performance touted in the magazines. As a result, Bede told buyers to consider the higher output engine options as the standard engine.

New Versions

Bede Aircraft was shipping out kits for a plane that the company couldn’t even reliably fly, yet Jim Bede already had new ideas to captivate pilots. In Mid-1973, Bede unveiled the factory-built BD-5D and once again it came with huge promises. Bede said that the BD-5D would be less than half as cheap as the cheapest new plane at the time but would go twice as fast. And you didn’t have to put it together yourself. But perhaps even more alluring was the second idea that Bede put out into the world: the jet-powered BD-5J. Gone was the unreliable Hirth snowmobile engine and in its place was a French-built Sermel TRS-18-046 turbojet that produced 225 pounds of thrust. And unlike the Hirth, these proved to be reliable. The BD-5J was so trustworthy, even, that Bede put a journalist at the controls just six months after the plane made its debut at Oshkosh. And in 1974, a trio of BD-5Js performed aerobatic feats at the Reading Air Show in Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, the propeller-driven BD-5 Micro was still encountering problems. Bede Aircraft was learning the hard way that snowmobile engines aren’t exactly built for aviation duty. Certainly, when you ride a snowmobile you aren’t keeping the engine at a constant RPM at a high altitude. Bede test pilot and engineer Les Berven at one point admitted that the company broke every part of those engines on their test stand. And they would break major components like cylinders, pistons, bearings, and crankshafts. That didn’t stop Bede and in 1974, prototype N503BD was built, and this one was able to be flown by journalists. As a byproduct of using a snowmobile engine, this thing had to be started like a lawnmower! And of course, the Hirth engines still had a knack for failing or shutting down, rendering the BD-5 into a pretty glider. The writer of the Aviation History Magazine piece gave another positive review of the BD-5, calling it responsive, extremely stable, and the highlight of their flying experience. Some reviewers felt similar, while others, like then Flying Magazine’s Jack Olcott, got to experience a forced landing after the Hirth engine quit. Reviews of the piston-powered BD-5 noted that when the engine did work, the aircraft also didn’t have the speed advertised. Unfortunately, Bede would never get the chance to iron out the engine issues.

Broken Promises

Hirth Motoren went bankrupt later in 1974 after having produced just 500 engines. This left Bede and most of his thousands of customers without an engine for their planes. It is estimated that some 5,000 kits were sold. An engine search led Bede to Zenoah in Japan. As today’s BedeCorp notes, the Zenoah replacement engine was supposed to be finished within nine months, but it took over three years. During this time, Bede continued development on what was supposed to be the factory-built BD-5D. And Bede was already thinking about the future, starting development on the BD-6 and BD-7. There was only one problem, the dwindling cash spent by Bede Aircraft was from the customers that plopped down orders for planes that most would never be able to finish, based on promises never realized. Bede had burned through $7 million in kit payments, $2.7 million in production model deposits, and the prop-driven BD-5’s engine was delayed for years. Bede Aircraft Corporation was out of money and worse, the Federal Trade Commission wasn’t fond that the money that should have been spent on BD-5 kits was spent on other developments. Jim Bede entered a consent decree with the FTC to stop accepting deposits for aircraft for 10 years. Bede’s bankruptcy was official in 1979, and owners of the 5,000 BD-5 Micro kits were left figuring out what to do with their planes.

Rise And Fall

Amazingly, many determined individuals weren’t willing to let the BD-5 Micro story end there. Roughly 150 to a few hundred BD-5s were completed, with perhaps 50 of them still flying. As it turned out, while the BD-5 was advertised as needing just 600 to 800 hours to complete, the reality was far worse. Those who managed to complete their BD-5s took up to around 3,500-working hours. It took some people almost a decade and tens of thousands of dollars to finish their BD-5s. Builders found out that these planes required a ton of custom fabrication for the drivetrain. Some kits were missing parts. And some found the forming, cutting, bonding, and riveting the raw materials together was harder than expected. A bunch of companies have sprouted up over the years to help get more BD-5s finished. Bede-Micro Aviation of California outfitted BD-5s with four cylinder Honda EB1 & EB2 engines meant for the Civic. BD-Micro Technologies out in Oregon carries the parts builders found missing in their kits. The company will even sell you a new BD-5 with improvements over the original Bede design. Builders have gotten creative over the years and all kinds of engines have powered BD-5s. The Subaru EA-81, some Volkswagen engines, and Rotax engines found BD-5 homes. Even newer and reliable Hirth engines have powered BD-5s. The Aviation History piece notes that some people got real wild with their engines, giving their BD-5s rotaries, Mercury outboards, and even a turboprop using gas generator from a Chinook. Unfortunately, while the BD-5 dream was finally realized for some, it would become a fatal nightmare for others. As of current, aviation safety database Aviation Safety Network tallies up 32 crashes of BD-5 aircraft, 26 of which have resulted in fatalities. Considering that perhaps as few as 150 were completed, that’s a huge chunk of planes to crash, often killing their sole occupant. On the list of fatal crashes for the BD-5 includes N503BD, the prototype flown by the press. And the latest recorded BD-5 crash was recorded in 2019. It too, was fatal. Many of these aircraft crashed on their very first flights, with an engine failure on takeoff followed by a stall noted as the cause. Even N503BD crashed due to a stall. Aviation History notes that three of the first BD-5As crashed and killed their pilots during takeoff. The fourth got into the sky only to crash on landing. Some of the problem is engine choice. The BD-5 was designed to have an engine that weighed 100 pounds or less. Those who did complete their planes often found themselves equipping their aircraft with a heavy powerplant. This had the impact of raising stall speeds and throwing off the aircraft’s center of gravity. Pilots testing the BD-5 have found that the aircraft will pitch up sharply after an engine failure, and if the pilot doesn’t get it under control in just a couple of seconds, it will stall. A stall at low altitude–such as takeoff and landing–can be a fatal event. And of course, you cannot discount the fact that these were put together by people of varying skill levels. Those people then worked without much instruction and made some things up as they went along. Jim Bede never stopped designing planes. After the FTC’s 10 years were up Bede opened Bede Jet Corporation. He then shocked the aviation world again with the BD-10. The aircraft was Bede’s attempt at the first supersonic general aviation jet-powered kitplane. Just five were built before Bede Jet filed for bankruptcy, and three crashed, killing their pilots. Bede continued to make striking designs, including a two-seat BD-5, a four-seat plane based on the two-seat design, and the BD-17, which touts easy construction for first-time builders. And the business kept going under a new name: BedeCorp. The BD-5J was even featured in the 1983 James Bond film, Octopussy.

Jim Bede passed in 2015. Today he’s remembered for some out-of-this-world plane designs and for kickstarting the kitplane genre. Bede was a plane enthusiast through and through, but he perhaps didn’t handle the business end the best. Awesomely, a handful of the BD-5J jets fly today, and one example is the World’s Smallest Jet thanks to its 358 lb weight. BedeCorp is still around, too, and you can get kits, parts, plans and more through the company. Some remember the plane for its wild design and Jim Bede’s enthusiasm, others for its crashes and Bede’s business management. But the BD-5 still has the same magic that it did 50 years ago. Pilots at air shows are still captivated by the tiny plane and its abilities. And thanks to enthusiasts, a pilot allured by the BD-5 today can buy a new one and not have to worry about a snowmobile engine failing immediately on takeoff.